Butcher, Baker, Dictator, Liberator

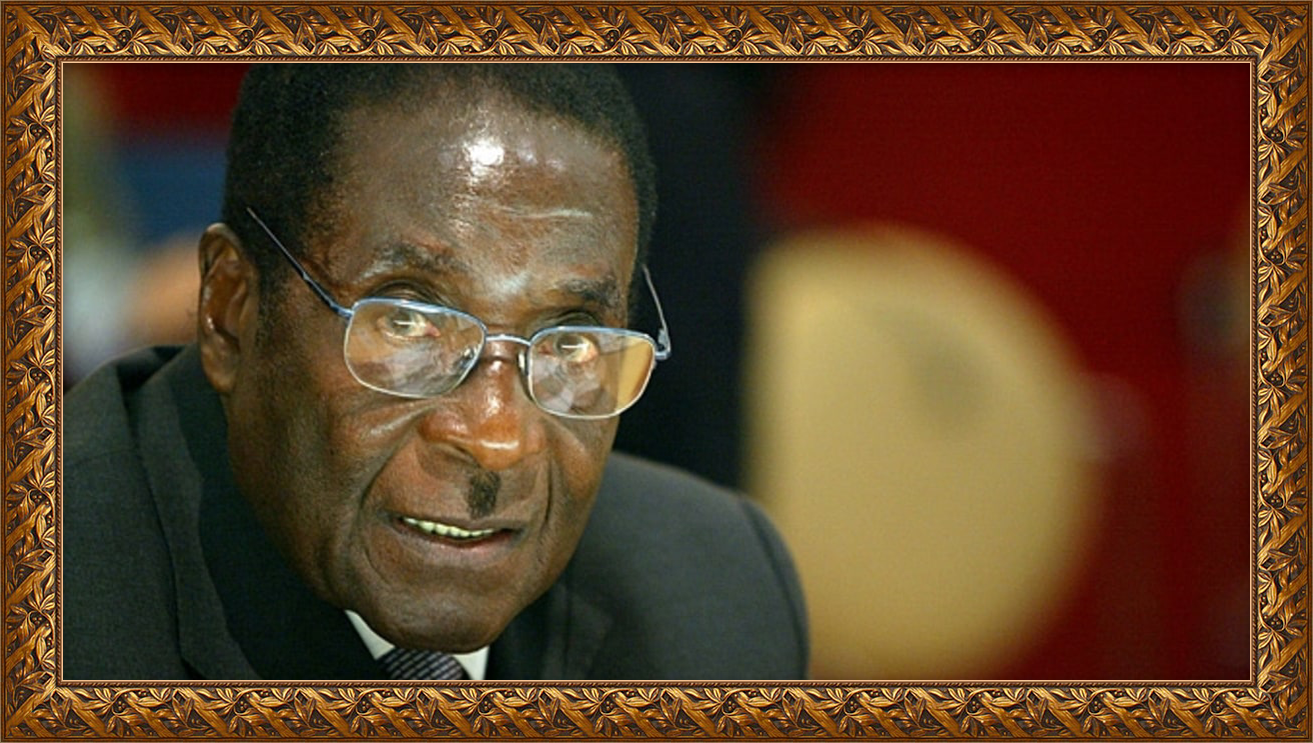

(Graphic: Brian Covert / Photo: Getty Images)

Robert Gabriel Mugabe, the former president of Zimbabwe, has died at age 95 in Singapore, while receiving medical treatment there over the past few months. Just as he was in life, Mugabe in death is a highly controversial political figure, with a legacy that is as much celebrated as castigated, as much praiseworthy as unworthy.

Among leaders of various nations, Mugabe’s credentials as a freedom fighter are being touted and memorialized as part of the wave of independence of African nations from European colonialism during the last century. “Under President Mugabe’s leadership, Zimbabwe’s sustained and valiant struggle against colonialism inspired our own struggle against apartheid and built in us the hope that one day South Africa too would be free,” Cyril Ramaphosa, the current South African president, said upon Mugabe’s passing.

Among common Zimbabwean people themselves, both those living within the country and those living across the border in South Africa, Mugabe’s passing elicited much more mixed reactions. “The death of Robert Mugabe today brings a sigh of relief to millions of Zimbabweans whose lives were wrecked by his totalitarian rule,” says Joseph Chirume, a black Zimbabwean. “Personally I say his passing away (not on) was long overdue. Good riddance.”

Why the wide chasm in perceptions of the man? After all, wasn’t Mugabe one of the great African leaders who led his country to liberation from the forces of European white supremacy? Wasn’t he also a leader with the blood of his own African people on his hands — the same people to which he always claimed he was devoting his life?

So, which one was it — a butcher of a leader who had innocent people within his own country killed or a baker who helped feed millions by leading an important breadbasket nation on the African continent? Which one was it — a liberator who was hailed in his day for taking a bush war directly to the doorstep of a European colonial power (Britain) on the African continent, or a petty-minded despot who persecuted his ethnic/tribal and political enemies and, in the end, became his own worst enemy?

Which one, you ask? The correct answer is: all of them. Robert Mugabe in his lifetime was all these contradictory things rolled into one, and often at the same time.

Mugabe had grown up under Zimbabwe’s own brutal brand of apartheid when his country was a colony, then known as Rhodesia, that was ruled by the British; he knew the hell of white racism well. He started out in his younger, more progressive-minded years as a staunch Marxist-Leninist intellectual who understood and embraced the socialist ideology of fighting down capitalism. He ended up many decades later, though, as little more than a right-wing nationalist who was overthrown in 2017 by members of his own military and security apparatuses — many of whom had fought in the war for Zimbabwe’s liberation back in the 1960s and 1970s.

Mugabe was in office as either prime minister or president from 1980 to 2017, the only national leader Zimbabwe had ever known in those 37 years. And he had little intention of stepping down even at that point or of sharing power with other younger people in his own party and other political parties in Zimbabwe. In his own mind, which increasingly grew frail and dimmed as he aged, he saw himself as Zimbabwe’s undisputed president for life. As Mugabe put it a few years ago: “I will be there until God says come, but as long as am alive I will head the country, forward ever, backward never.”

He was the best of what Zimbabwe stood for as a young new nation; he became also the worst of it.

I witnessed some of this firsthand during a brief time I spent in Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe, in late 1989/early 1990. (I had been planning to report as a journalist on the situation in neighboring South Africa, though I never did make it over the border.) For a close encounter I had with Mugabe himself, see my earlier blog posting.

I was in Zimbabwe when the U.S. government under president George H.W. Bush (Bush Senior) invaded the Central American nation of Panama on 20 December 1989. Mugabe spared no niceties in publicly denouncing this violation of international sovereignty by the U.S., a denunciation I was personally glad to see.

At the same time, the smell of domestic political corruption was in the air back then, and Mugabe was tainted by that. White Zimbabweans thought Mugabe was the devil incarnate; they absolutely hated and feared him. Black Zimbabweans, however, generally tended to give Mugabe the benefit of the doubt: “I think Mugabe is honest, but it is the people around him who are corrupt”, one black Zimbabwean told me. That was typical of the people’s thinking around that time. But that benefit of the doubt didn’t last too long, as Mugabe went on to operate his political party’s machinery with an iron hand.

Western countries were mostly silent back in the 1980s when tens of thousands of innocent people of Zimbabwe’s Ndebele ethnic group were slaughtered by the new nation’s military forces, reportedly on the orders of Mugabe himself, who belonged to the rival Shona ethnic group, the majority.

The West, on the other hand, reacted with hypocritical horror when Mugabe gave his blessing in the early 2000s to white Zimbabwean farms being taking over by black Zimbabweans, even if it meant killing a few whites in the process. That was the nationalistic direction Mugabe was increasingly moving in as president, but it was certainly nothing new. He had been going in that direction since just after Zimbabwe had gained its independence from Britain in 1980.

When I was in Zimbabwe in 1989-90, the food situation there was already severe. I saw with my own eyes how often the shelves of local grocery shops would be bare and there would be no bread or other daily necessities available for people to buy. Ten years after that, Mugabe’s expropriation of white farms, among many other heavy-handed policies, had sent Zimbabwe’s food security and overall economy spiraling downward into disaster.

Today, Zimbabwe does not even control its own monetary system. The United States dollar ($) has been adopted as the official currency for all government transactions in Zimbabwe. As of June of this year, the inflation rate in Zimbabwe stood at 175 percent, leading to mass unrest across the country and especially in Harare, the capital city I remember so well.

This is the legacy that Mugabe leaves behind with his recent passing in Singapore at age 95, having claimed publicly in the past that “Zimbabwe is mine”. He also leaves behind the legacy of a determined freedom fighter in his country’s history. It is a mixed bag, to be sure, and that is why we are seeing such wildly diverging views of Mugabe’s death around the world. And it is likely to stay that way for a long time.

As for me, I stand on the side of the common people of Zimbabwe — the black majority of that country — and put my faith in them because they are the ones who really knew Mugabe, faults and all. They knew the best and worst of Mugabe firsthand from experience over many decades, and they are ultimately the ones who should judge what that means to their nation and to the world.

Robert Gabriel Mugabe wasn’t the first baker-turned-butcher, the first liberator-turned-dictator, in human history. And he won’t be the last. But that does not excuse his past crimes, and it does not give him a free pass into the life hereafter either. Before he goes floating past the blaring trumpets and inside the heavenly gates, he will surely have to do some explaining to his Roman Catholic God as to why it was necessary for this president in his lifetime to help destroy his own people in order to set them free.